The Chemistry of Relevance: Building Institutions That Don’t Burn Out

The Chemistry of Relevance: Building Institutions That Don’t Burn Out

By Greg Pillar

My path in higher education started in the classroom, the field, and the lab, teaching environmental science and chemistry. One of the memorable reactions I remember sharing with students was what happens when luminol meets hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a catalyst, usually iron, often from blood. A dazzling blue glow appears. You’ve likely seen this reaction in crime dramas, where investigators use it to uncover invisible traces at a scene. But in real life, as in fiction, the luminescence doesn’t last. Within roughly 30 seconds it fades, just long enough to capture a picture as evidence. That brief flash of light may be captivating, but without the right conditions, it never becomes something more.

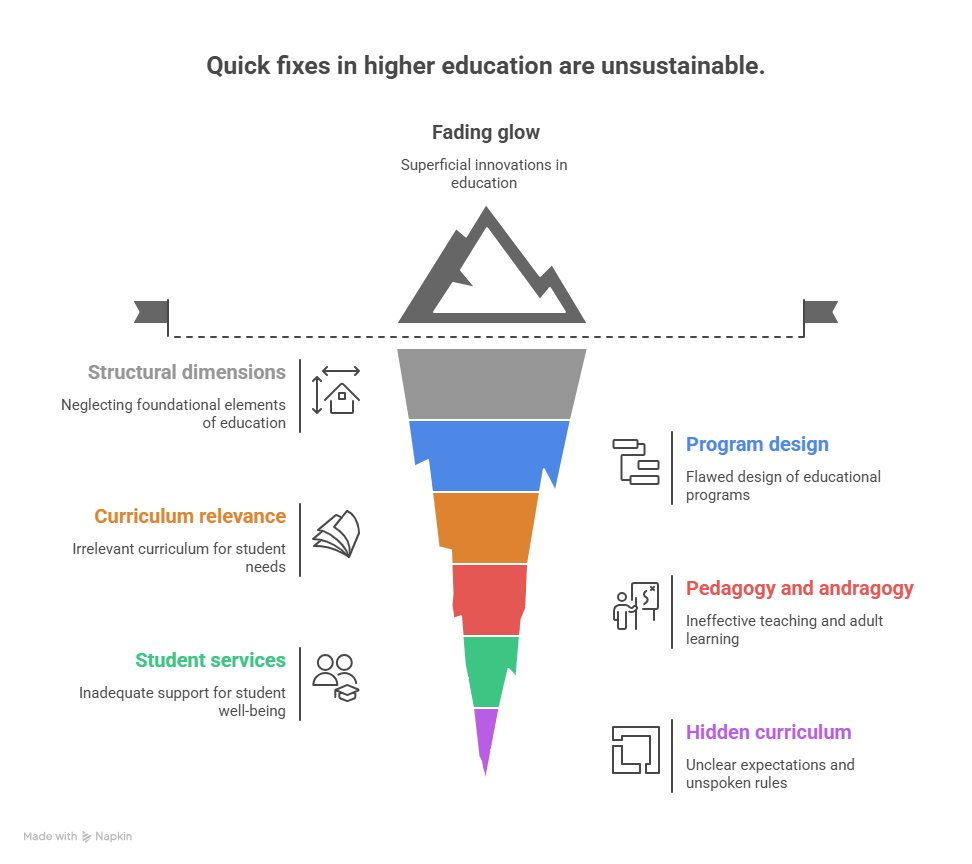

Higher education has its version of this, trying to find the right catalyst that, when coupled with attractive programs, a distinctive campus experience, notable advertising, and a clever enrollment strategy, delivers the bright glow of growth, more students, more revenue, maybe even a bump in the endowment. But most methods are superficial. A curriculum tweak sold as “industry-aligned,” the addition of a trendy program, or increased flexibility in modality or student services, all framed as innovation. For a moment, it works. When connected to the marketing and enrollment teams, there’s a flash of interest. A bump in inquiries and applications. Maybe even some growth in deposits and enrollment. But it rarely lasts.

Without sustained work on the structural dimensions, program design, curriculum relevance, pedagogy and andragogy, wraparound student services, and the ease of navigating higher ed’s hidden curriculum and often unnecessary red tape, the glow fades quickly. No real reaction, no sustained light, and thus no traction. Just another attempt at transformation that burns out before it ever takes hold. At what cost? How much money and time was lost? These quick fixes aren’t just pedagogical gambles; they’re financial ones. Resources get poured into surface-level innovations without addressing the deeper causes of enrollment and retention issues. Institutions spend money chasing what may be hoped for as long-term growth, but in reality nothing more than a flash in the pan. All the while the underlying structures and systems are broken. Think of what follows as a braid: the spark of new and revised programs, the systems that sustain them, and the alignment that gives them meaning. The first strand is understanding the luminol moment, and how quickly the glow fades without the right conditions.

We’re clearly seeing more and more examples of a college or university cutting or consolidating programs. This isn’t just a trend towards struggling small privates. Larger, established publics, Ball State, Purdue, Marquette, and Indiana University, are also making cuts. And while some of this is necessary portfolio realignment, much of it feels more reactive than proactive. Desperate. Decisions made in darkness, without the glow.

At first glance, the logic seems sound: low-enrolled programs aren’t sustainable, so cut them. But that’s a shallow analysis. Some programs may still be relevant but need rethinking. Others are solid in content but outdated in delivery or disconnected from student interests and labor market needs. The better questions are: are we maintaining the conditions that make programs glow in the first place? Are we committed to the work needed to make the flow last?

Even more urgently, institutions must build programs that can sustain their relevance, their glow, in a world defined by constant change.

If every institution rushes to add the same “high-demand” programs, we’ll flood the market. Saturation will follow, outcomes will flatten, and we’ll be back at the drawing board, facing the same problems in new packaging. Instead of reactive additions, colleges and universities need proactive design: a portfolio built not just for today’s trends, but for tomorrow’s unknowns.

Nicole Poff, host of EdUp: Curriculum podcast, has been one of the sharpest voices pressing for this deeper inquiry. In post after post on LinkedIn, she questions why academic freedom is used as an excuse to resist curricular change. Why do we pretend the product doesn’t need rethinking? Why do we cling to the idea that enrollment issues can be solved with better messaging, rather than better programs?

She’s right, this isn’t a marketing issue or enrollment issue (not that those offices are not important and if poorly led can be quite detrimental). It’s a product issue.

The glow can’t be sustained by marketing alone. It requires a product that’s relevant, accessible, and where completion is clearly attainable. That’s the second strand of this braid: product clarity. Your programs are your institution’s value proposition. But even the most in-demand, market-aligned programs will fall short if students can’t find their way through them, if the red tape is too thick, the hidden curriculum too opaque, or the support too shallow. The academic core is critical, but it doesn’t operate in isolation. Services and student experience are not accessories; they’re part of the catalytic mix.

Leaders like Melik Peter Khoury (Unity Environmental University), Brad Fuster (San Francisco Bay University), Michael Avaltroni (Fairleigh Dickinson University), and Richard Pappas (Davenport University) understand this. Their strategies start with strong programs and a structure that helps students persist, progress, and succeed. That’s the combination that sustains the glow, not just flashy new offerings, but systems that help students finish what they start.

That brings us to the third strand of this braid: coherence and core alignment. Systems, governance structures, and delivery mechanisms either enable change or prevent it. Agility is required not just in the curriculum, but in the way decisions are made, programs are approved, and innovation is supported. Most shared governance structures were built for stability, not adaptability. As Brian Rosenberg observes in Whatever It Is, I’m Against It, higher education tends to privilege deliberation over action. The result is a slow, often rigid system that struggles to respond to evolving student needs, new delivery models, or emerging industry demands.

Look at the institutions led by the presidents and provosts noted above: Unity Environmental University, San Francisco Bay University, Davenport University, Fairleigh Dickinson University. Their progress is much more than launching new programs. It is rethinking how operationally their institutions function all with the student front of mind.. They’re building systems that allow for experimentation, piloting, and responsiveness. The goal isn’t to chase what’s hot. It’s to create a foundation where programs can adapt without crisis, where relevance isn’t a lucky spark, but the result of deliberate, sustainable design.

When institutions lack alignment between their vision, values, and execution, even strong programs lose momentum. The glow fades not because the content is weak, but because the systems can’t sustain it, the catalytic mixture is gone. Coherence across academics, operations, and student experience is what allows relevance to persist, even as conditions change.

It’s the challengers of convention who help move higher education forward, those willing to question long-held assumptions and reckon with what no longer works. In addition to the voices already noted, Matt Alex urges institutions to reimagine outdated operating models through a student-centered lens. Rebeka Mazzone warns of economic instability and the lack of financial forecasting. Gary Stocker and Matt Hendricks unpack the brutal math of institutional survival. Elliot Felix calls out the operational and service barriers that quietly, and sometimes visibly, push students out. From curriculum to finance to student experience, these voices converge around a simple truth: standardization isn’t the enemy of creativity or agility, employer input doesn’t undermine academic integrity, and modernization isn’t code for selling out. The real risk isn’t change; it’s the refusal to adapt while the rest of the world evolves and moves on.

And let’s be really clear: this isn’t a marketing or enrollment issue. A new logo or more automated emails/phone calls won’t fix a bloated curriculum or program portfolio. Better slogans won’t mask broken advising, outdated course delivery, or poor financial projections based on questionable data. Like a luminol reaction, programs and institutions only shine under the right conditions. When the structure, support, and design are misaligned, the result isn’t innovation, it’s failure to launch.

Cutting programs without a process for maintaining relevance is like turning off the lights in a lab right after a failed reaction. You miss the chance to examine what went wrong, to recalibrate, to learn. The glow fades, and so does the opportunity for renewal. And even when cuts are necessary, they’re often made too late, delayed by indecision or resistance, limiting the institution’s ability to pivot or invest in what’s next.Program and institutional evaluation have to go deeper than enrollment data.

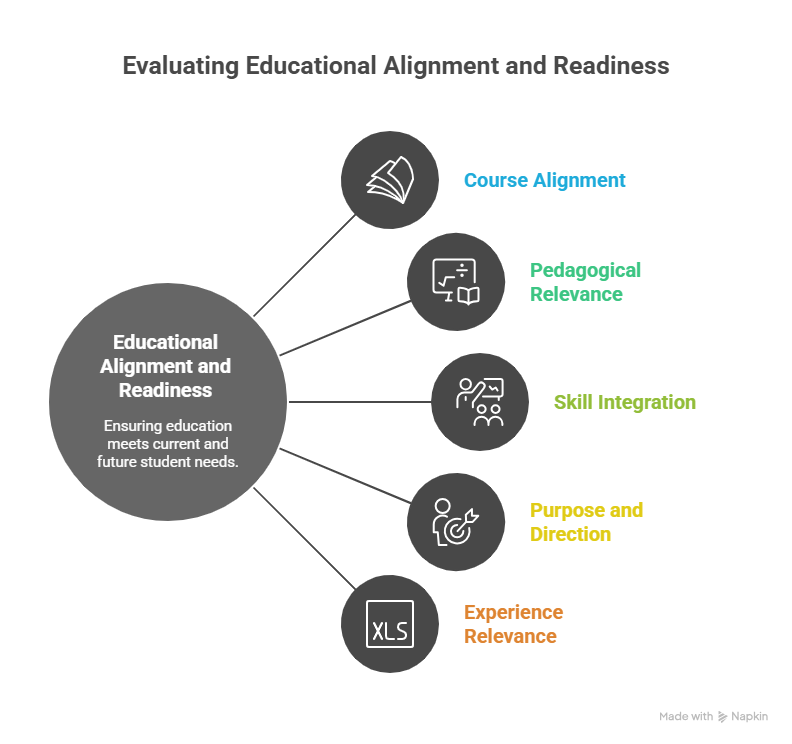

Ask:

- Are our required courses aligned with the competencies and skills students need today and tomorrow?

- Is our pedagogy (and andragogy) current, inclusive, and adaptable across learning modalities?

- Do we have systems in place to rapidly integrate relevant, career-connected skill development?

- Are students leaving not just with content knowledge, but with clarity of purpose and direction?

- Does the student experience, from course navigation to support services, match the realities they’ll face after graduation?

This is not an exhaustive list, but you have to wonder how many faculty and staff, and by extension institutions, answer “no” to most or even all of those questions? The institutions doing this deep work may face temporary financial or even operational discomfort. But unlike the gimmick-driven approaches, their investment pays off in long-term viability. They’re not scrambling to survive; they’re building toward a sustainable future where they are projecting five years out rather than year to year. The strongest institutions will treat their academic portfolios as living systems. Dynamic. Iterative. They’ll build structures that make reflection routine, not just a reaction to budget stress. They’ll empower faculty to lead renewal, not fear it. And they’ll resist the temptation to chase shiny new programs without doing the hard, necessary work to sustain the ones that matter.

They’ll stop chasing after the glow.

They’ll learn how to make it last.

In reality, the glow, like many reactions, fades or reaches equilibrium and stagnation. But through chemistry and a little engineering reactions can be designed to last. Under the right conditions, we can sustain and even scale them.

The Haber-Bosch process, detailed in The Alchemy of Air by Thomas Hager, transformed nitrogen fixation into a continuous, scalable reaction. It revolutionized agriculture and fueled wartime industry. That’s a tale (and metaphor) for another day. But the broader lesson applies with the right structure, processes, and systems in place, reactions that once seemed fleeting or small scale (like Haber-Bosch) can endure.

It’s no longer viable to chase short-term glow. Higher education must be designed for sustained light.